Here is what every React Developer needs to know about TypeScript - Part 2

Welcome to the second part of this series on TypeScript, first part was about why to use TypeScript in general, how to use it and an overview of the language. In this second part you can take a closer look at how to use TypeScript in React and how to solve the different challenges you will face when trying to develop an app with React and TypeScript.

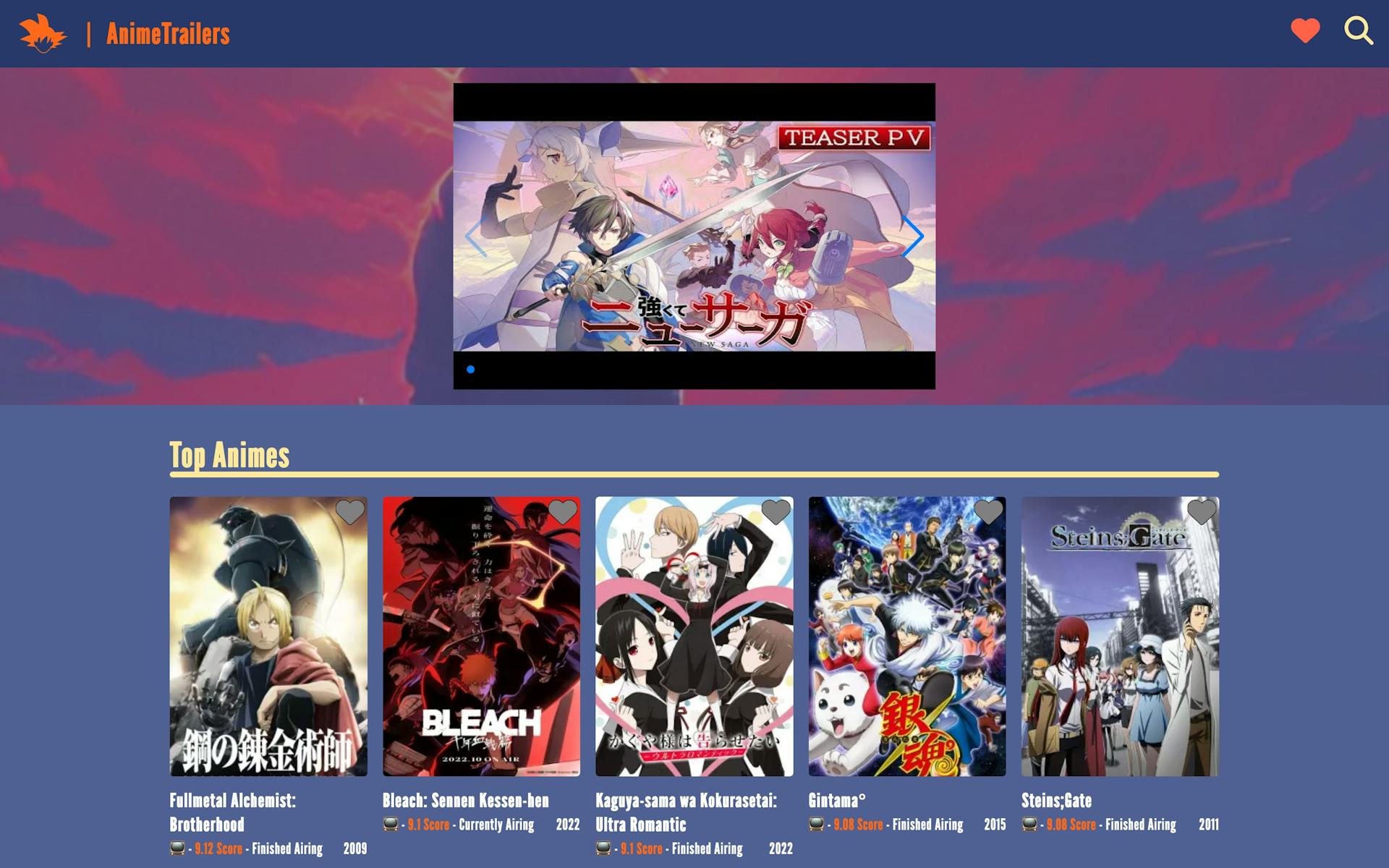

AnimeTrailers aka the Example Project

As always a working example project is provided with the article to have real code to refer to and test real implementations.

In this case I have built AnimeTrailers a dummy application that thanks to JikanAPI provides a list of anime and basic information to watch the latest trailers of your favourite anime.

Resources

- Example project source code

- Create React App + TypeScript + ESLint + Prettier Boilerplate

- Vite + TypeScript + ESLint + Prettier Boilerplate

- TS Handbook

- Here is what every React Developer needs to know about TypeScript - Part 1

Why React + Typescript

If you want to know why bother dealing with TS I recommend reading that section from the first part, the same arguments can be used here to defend its use in combination with React.

It's also worth adding that most of the TypeScript code in React is inferred, so in addition to the fact that everything will be examined here in detail most of the time you'll be fine with inferred types and the types already provided by React.

Setup

Create React App

For CRA users, you only need to specify the template:

npx create-react-app my-awesome-project --template typescript

Vite

Creating a TypeScript project with Vite is as easy as using the CLI and choosing the TypeScript template.

npm create vite@latest my-awesome-project

Add to existing project

If you want to add TypeScript to a project that is in JavaScript just add TypeScript as a development dependency.

npm install -D typescript

I must warn you that if this is your first encounter with TypeScript I do not recommend that you try it on a project that you have already built, because your experience will be to constantly think that you have something working and that it is all just more work for nothing, and that cannot be further from the real benefits of TypeScript.

Typing Component Props

The first and most common scenario when using TypeScript in a React project is to write the props for a component.

To correctly write the component props you need to specify what properties you are accepting on the component, the type and if it is required or not.

// src/components/AnimeDetail/Cover/index.tsx

type CoverProps = {

url: string

}

export default function Cover({ url }: CoverProps) {

// ...

}

We only use a url prop which is a string and is a mandatory prop.

Another example with more props and optionals:

// src/components/AnimeDetail/StreamingList/PlatformLink/index.tsx

type PlatformLinkProps = {

name: string

url?: string

}

export default function PlatformLink({ name, url }: PlatformLinkProps) {

// ...

}

With ? we are indicating that it is an optional parameter, so TypeScript know that the type of url in this case will be string or undefined. Also, consumers of this component will not get an error if they do not pass a url prop to the component.

If you have read my previous article you will already be familiar with types, but let's look at one last, more complex example:

// src/components/AnimeDetail/Detail/index.tsx

type AnimeType = 'TV' | 'Movie'

type DetailProps = {

liked: boolean

toggleFav: () => void

title: string

type: AnimeType

episodeCount: number

score: number

status: string

year: number

votes: number

}

export default function Detail({

liked,

toggleFav,

title,

type,

episodeCount,

score,

status,

year,

votes,

}: DetailProps) {

// ...

}

This time you can see a myriad of types, including a function and a custom type AnimeType.

So, to summarise, writing props is useful for:

- Actual validation of the prop type from the consumer's side.

- No more guessing what a component needs.

- No more opening components source code to check what it does with the data.

- Auto-complete and document.

- Know directly from the consumer what props and values are needed through auto-completion without knowing in advance.

Of course, this will absolutely shine on complex components and third party components that come from fancy libraries you use in your project.

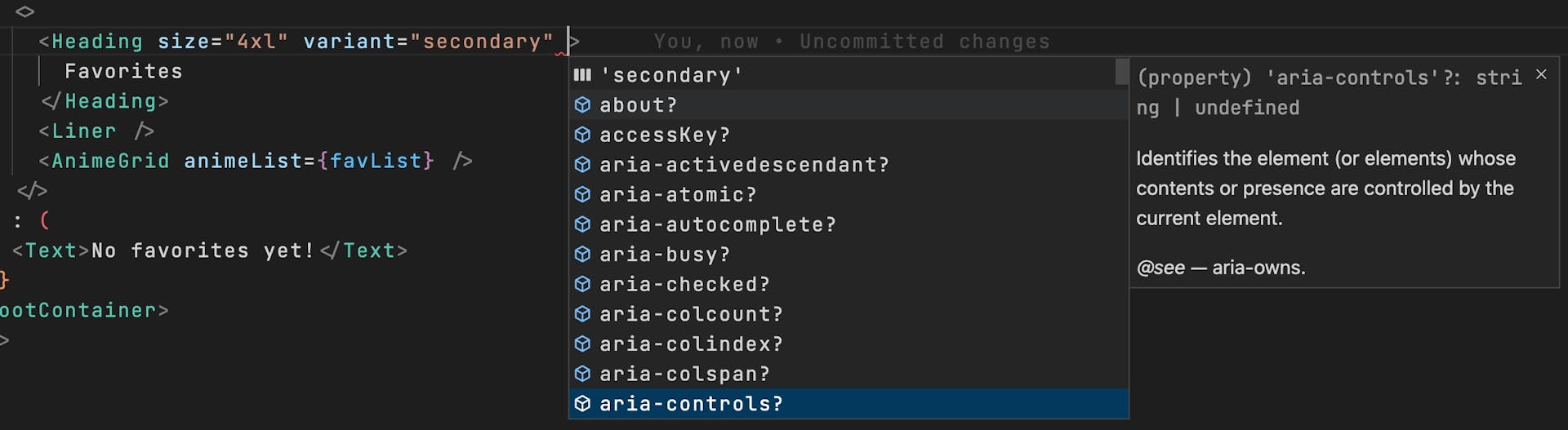

React Built-in Types

With React and a lot of libraries you will find tons of pre-built types to ease your experience as a developer. For example in React it is quite common to have the following component:

// src/components/Layout/index.tsx

type LayoutProps = {

children: React.ReactNode

}

export default function Layout({ children }: LayoutProps) {

// ...

}

A custom React component that receives other element as children. For those cases you will define children as a ReactNode type.

A warn about React.FC && React.FunctionComponent

You may find code with this syntax for declaring component props:

type PlatformLinkProps = {

name: string

url?: string

}

const PlatformLink: React.FC<PlatformLinkProps> = ({ name, url }) => {

// ...

}

This code works using React.FC, or its longer version React.FunctionComponent, but you should know that it has some disadvantages and that is why we are not using it in this article:

- You have to use a function expression and you can't use a function declaration, this is a minor point, but I built all components with function declaration on purpose.

- You can't use generics (we'll see this later).

- In the past this caused your props to indirectly accept the

childrenproperty and in this component you don't use it. This was true until React 18, nowadays it doesn't apply.

Return type of a React component

Last piece of the puzzle, what does a component return? You can use React's built-in types React.ReactElement, React.ReactNode and JSX.Element:

export default function Favorites(): JSX.Element {

// ...

}

To summarise the answer from this section: let TypeScript automatically infer the return type. If you need a detailed list of the differences between those 3 types I suggest you have a look at this SO post

Types vs Interfaces

Part 1 already covered this but as a reminder you should follow this rule of thumb: If you write object oriented code - use interfaces, if you write functional code - use type aliases in combination with Use interfaces for public API libraries and types for components, state, JSX, etc. For that reason I included in the boilerplates that ESLint autofixes interfaces to types.

If you want to go deeper into the differences you can read this post in TS Handbook but nowadays most of the features present in an interface are in a type as well and vice versa.

TLDR; types are more restricted and interfaces can be opened and add more properties.

Combinations with Template Literals

Inside AnimeTrailers I have included a simple custom UI that will be useful to demonstrate cases like this, you can check the different simple components in src/components/UI but most of them will be explained through this guide.

Let's take a look at the Position custom component:

// src/components/UI/Position/index.tsx

import React from 'react'

import { StyledPosition } from './StyledPosition'

type VPosition = 'top' | 'bottom'

type HPositon = 'left' | 'right'

export type PositionValues = `${VPosition}-${HPositon}`

type PositionProps = {

children: React.ReactNode

position?: PositionValues

}

export default function Position({

children,

position = 'top-right',

}: PositionProps) {

return <StyledPosition position={position}>{children}</StyledPosition>

}

Position is a simple component to use with any other component with absolute positon and place it on any of the four edges with top-left, top-right, bottom-left and bottom-right.

Creating a new type with template literals has no secret if you are already using it in JavaScript, the clever trick here is when you combine template literals ${VPosition}-${HPositon} with union types top | bottom like in the example above, TypeScript will generate all possible combinations of both, so we can generate the four different values we need.

Exclude

Let's take the previous example and add more values to the union:

type VPosition = 'top' | 'middle' | 'bottom'

type HPositon = 'left' | 'center' | 'right'

export type PositionValues = `${VPosition}-${HPositon}`

This template literal will generate all possible combinations of unions, so we will have "top-left" | "top-center" | "top-right" | "top-left" | "center-left" | "center-right" | "bottom-left" | "bottom-center" | "bottom-right".

There is one case that is a bit strange, middle-center. In this case you may want to simply put center, in which case Exclude is very useful.

type PositionValues =

| Exclude<`${VPosition}-${HPositon}`, 'middle-center'>

| 'center'

Now PositionValues will generate "center" | "top-left" | "top-center" | "top-right" | "middle-left" | "middle-right" | "bottom-left" | "bottom-center" | "bottom-right".

With exclude you can remove the middle-center and add center afterwards with a union.

Custom HTML Components

If you want to create a component that behaves like an input but you don't want to write every single property and function of the input HTML, you can achieve this with:

// src/components/UI/Input/index.tsx

import React from 'react'

import styles from './StyledInput.module.css'

type InputProps = React.ComponentProps<'input'>

const Input = React.forwardRef(

(props: InputProps, ref: React.Ref<HTMLInputElement>) => {

return <input {...props} className={styles.StyledInput} ref={ref} />

}

)

export default Input

With React.ComponentProps you can specify which element you are basing your new type on and get everything a real HTML input has to create a custom UI component. But what happens when you want to override some of these properties or forbid their use?

Omit

Let's take a look at the Tag UI component:

// src/components/UI/Tag/index.tsx

import React from 'react'

import { StyledTag } from './StyledTag' // aka a styled span

type TagProps = {

variant?: 'solid' | 'outlined'

text: string

} & Omit<React.ComponentProps<'span'>, 'children'>

export default function Tag({ text, variant = 'solid' }: TagProps) {

return <StyledTag variant={variant}>{text}</StyledTag>

}

In this case, this component explicitly passes a text to display as children of the component. You may not want consumers of this component to use the original children, so you can omit that property from the collection given by React.ComponentProps.

Typing Hooks

Now let's dive into how to write each of the most commonly used hooks in React.

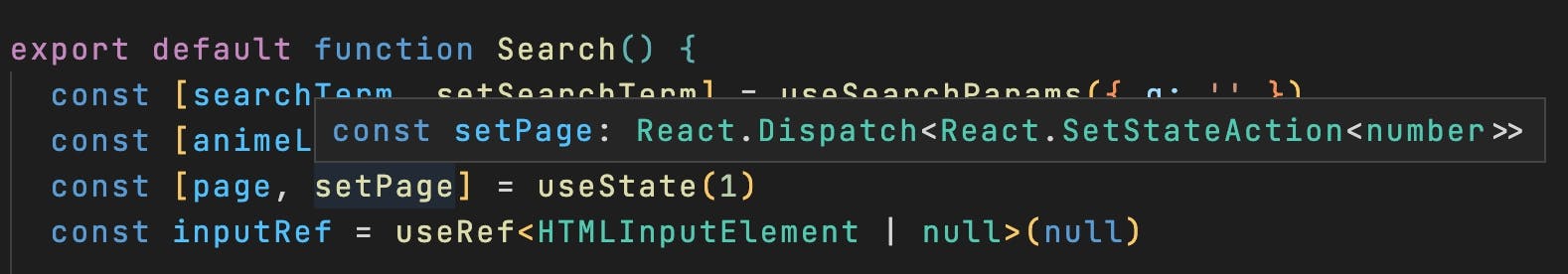

useState

In most cases, typing useState will not require anything from you, because TypeScript will try to infer the type, in other scenarios, e.g. when the initial value is different from future values, you need to specify it directly.

// src/pages/Search.tsx

export default function Search() {

const [animeList, setAnimeList] = useState<Anime[] | null>(null)

const [page, setPage] = useState(1)

// const [page, setPage] = useState<number>(1)

// ...

}

From the state page the type is inferred as a number based on the initial value provided, it will be exactly the same as the commented version. Also state setters are automatically typed as React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<number>> with number replaced by the inferred/specified type.

On the other hand animeList without any explicit type would be only null, which is true before the component gets the necessary data but will eventually contain a collection of Anime types for which you must explicitly set the type with a union of the two possible types.

Beyond setting the type to null for initial control states in useState there are other similar solutions, such as:

export default function Search() {

// const [animeList, setAnimeList] = useState<Anime[] | null>(null)

const [animeList, setAnimeList] = useState<Anime[]>([])

const [anime, setAnime] = useState<Anime>({} as Anime)

// ...

}

*Important to take a closer look at anime, setAnime line, in that case it works because it is not a collection, is a single element.

The main difference with these additional solutions is that you are not 100% honest with the compiler. You are assuming that you will have a value with that shape, and that has an implicit risk.

export default function Search() {

const [anime, setAnime] = useState<Anime>({} as Anime)

// ...

return <div>{anime.coverURL}</div>

}

If you do not provide a correct value with this option this may explode at runtime.

Passing state as props

Quite often you may need to pass state down in the hirearchy and delegate to a children when a state is read or set. You will need to write the props for that component with state types in mind.

type FancyComponentProps = {

anime: Anime,

setAnime: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<Anime>>

}

const FancyComponent = ({anime, setAnime}: FancyComponentProps) => {

// ...

}

It is best to understand what types you need to pass but if you have difficulty with that, you can check the current state variables and the IDE will tell you what you need to pass.

useReducer

At this point you have mostly all the tools to correctly define the types for useReducer.

For the following example although I have simplified it here and we will cover the actual code in the Generics section.

// src/hooks/useFetch.ts

const enum ACTIONS {

LOADING,

FETCHED,

ERROR,

}

type State = {

data?: Anime[]

loading: boolean

error?: Error

}

type Action =

| { type: ACTIONS.LOADING }

| { type: ACTIONS.FETCHED; payload: Anime }

| { type: ACTIONS.ERROR; payload: Error }

const initialState: State = {

loading: true,

error: undefined,

data: undefined,

}

const fetchReducer = (state: State, action: Action): State => {

switch (action.type) {

case ACTIONS.LOADING:

return { ...initialState }

case ACTIONS.FETCHED:

return { ...initialState, data: action.payload, loading: false }

case ACTIONS.ERROR:

return { ...initialState, error: action.payload, loading: false }

default:

return state

}

}

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(fetchReducer, initialState)

As always, you get a status and a dispatch from useReducer when you provide a reducer function and an initial state. You don't need to do anything in the useReducer itself, but you must write the state and actions because this will define how the state and dispatch will behave.

initialState

For the initial state you can simplify the process and instead of creating a State type, you can use typeof initialState whenever you need to define a type based on the initial state.

const initialState: State = {

loading: true,

error: undefined,

data: undefined,

}

const fetchReducer = (state: typeof initialState, action: Action) => {

// ...

}

The drawback of this version is that it does not control the future values of data and error. This may work when the type is always the same but it is not the case here so you can use a custom State type for that.

Actions

You have to specify which actions the reducer will be able to handle, and that is done with unions. The enum part is entirely optional, but it helps to be less error-prone than writing strings in several places.

reducer function

You only have to specify the types of the params passed to the function, which are in fact the ones you created in the previous steps.

Passing as props

Again, if you want to pass something from useReducer as a prop, you will have to write the consumer props accordingly.

statewill be the type you have defined in yourinitialStateand/or a customStatetype as in the example above.dispatchwill beReact.Dispatch<Action>whereActionis the custom type for actions.

useContext

The context in the example project is used to manage a list of anime you like and toggle the state at different points in the application. At this point useContext will have no secret for you because it is simply a combination of what you have seen so far but let's look at an example:

// src/context/FavContext.tsx

type FavContextType = {

favList: Favorite[]

// setFavList: React.Dispatch<React.SetStateAction<Favorite[]>>

toggleFav: (id: number, favorite: Favorite) => void

}

export const FavContext = createContext({} as FavContextType)

export const FavContextProvider = ({ children }: FavContextProviderProps) => {

const [favList, setFavList] = useState<Favorite[]>([])

const toggleFav = (id: number, favorite: Favorite) => { /* ... */ }

// ...

return (

<FavContext.Provider value={{ favList, toggleFav }}>

{children}

</FavContext.Provider>

)

}

useContext follows the same rules as useState for typing. In this case, the initial value will be null but we trick TypeScrpt with as on createContext and define an object that will contain an array of favourite animes and a function to toggle.

Commented you have the typical setter scenario in case you need it.

For the rest of the code, you already learned useState in the previous section so nothing new, with the Favorite type useState will determine the necessary types and those types will be available directly on the consumer side.

// src/components/AnimeDetail/index.tsx

const { favList, toggleFav } = useContext(FavContext)

useRef

useRef can be used in two different ways, so the typing will be slightly different in each case.

DOM references

One of the uses of useRef is to keep a reference to a DOM element.

In the example project you'll find this for infinite scrolling by holding a reference to an observable of the last item in the anime list, so you can know when the user is viewing that item in the viewport and trigger a new fetch.

Let's look at a shorter example of useRef for the DOM reference, but you can check the full version of the useRef + observer

const myDomReference = useRef<HTMLInputElement>(null)

useEffect(() => {

if(myDomReference.current) myDomReference.current.focus()

}, [])

A typical case might be when a page loads and you want an automatic focus on an input. Just specify the type of the DOM element being referenced, in this case HTMLInputElement.

Some considerations about the above code:

- The hook will return a read-only

currentproperty. - You don't need to manually write

current, React will handle it throughReact.RefObject<HTMLInputElement>in this case. - If the DOM element is always present, you can set the initial value to

null!and avoid the if check.

Mutable references

The second use of useRef is when you want to keep mutable values between renders, e.g. in cases where you need a unique variable for each instance of a component that survives between renders and does not trigger a re-render.

const isFirstRun = useRef(true)

useEffect(() => {

if(isFirstRun) {

// ...

isFirstRun.current = false

}

}, [])

Some considerations you will notice compared to the previous example:

- You can now mutate the value inside

current. - React provides

React.MutableRefObject<boolean>is now aMutableRefObjectinstead ofRefObject.

Forwarding ref

If at some point you need to pass a reference to an HTML element as in the useRef section writing the props for that component will be slightly different:

// src/components/AnimeGrid/Card/index.tsx

const Card = React.forwardRef(

(

{ id, coverURL, title, status, score, type, year }: CardProps,

ref: React.Ref<HTMLImageElement>

) => {

// ...

})

To pass the reference you will need to wrap your component with React.forwardRef and that will inject along with the regular props of the component the ref which will be any HTML element wrapped in the React.Ref type.

In this case we know the type of the HTML element we are forwarding to, but if this is not your case, this might be a good time to use generics.

Generics

If you need to review what generics are, be sure to check the part 1 under Generics section.

Let's imagine we want to create a custom UI component by wrapping existing HTML elements but giving it a set of custom properties as most component libraries do.

Most of these libraries also provide the flexibility to decide which HTML element is finally rendered with an as property and that is exactly the case for the Text UI component. This Text UI component is used to display any text with a set of sizes and colors, plus we want to allow the user to choose any HTML element they need, not restrict themselves to a single p or span.

In this scenario you don't know in advance what element the consumer will pass to your component, so you need to use generics to infer the type to whichever one they pass.

So the prop types for the component will be:

// src/components/UI/Text/index.tsx

type TextOwnProps<T extends React.ElementType> = {

size?: 'xs' | 'sm' | 'md' | 'lg' | 'xl'

variant?: 'base' | 'primary' | 'secondary'

as?: T | 'div'

}

type TextProps<T extends React.ElementType> = TextOwnProps<T> &

React.ComponentPropsWithoutRef<T>

export default function Text<T extends React.ElementType = 'div'>({

size = 'md',

variant = 'base',

children,

as = 'div',

}: TextProps<T>) {

// ...

}

Let's examine in detail what happens in the example above:

- We use

Tfor generics here but you can use any name you want. - T extends from

React.ElementTypewhich is the most generic type for HTML elements, so we know that whatever is passed to the component is based on an HTML element rather than a manually typed union of all possible HTML elements. - The second type

TextPropsis used for two things:- We need extra properties depending on the type of HTML element, when a consumer uses the Text component as a

labelwe want to check and suggest different properties than when it is aspanfor that we need to useReact.ComponentPropsin this case we don't need references so we explicitly use the typeComponentPropsWithoutRef. React.ComponentPropsalso provides thechildrenprop so you don't need to include inTextOwnProps.- There is no need to deal with

Omitor other exclusion techniques becausechildrenis not modified or overwritten by anyTextOwnPropsprops.

- We need extra properties depending on the type of HTML element, when a consumer uses the Text component as a

With this example, we have a very flexible component that is correctly typed and provides a good developer experience.

Within the example project you can examine the different custom UI components to check the implementation following this same pattern.

Typing Custom useFetch Hook

In the example project I have included a simple hook to get the data and use localStorage as a temporary cache so as not to exceed the API limit, it is not a big deal but I think it is a complete example of everything explained in this article.

Let's take a look at some parts of that hook but I encourague you to watch the real file and try to understand everything with the different sections explained in this article.

// src/hooks/useFetch.ts

type State<T> = {

data?: T

loading: boolean

error?: Error

}

function useFetch<T = unknown>(

url?: string,

{ initialFetch, delayFetch }: Options = { initialFetch: true, delayFetch: 0 }

): State<T> {

// ...

}

- The hook receives a generic type that you can't know in advance what kind of data it will handle.

- The hook accepts

urlon where to do the fetch and options to decide if the hook does an initial fetch and if there is a delay between fetches. - The

optionsobject have default values if nothing is provided. - The hook returns a

Stateof the type specified by the consumer via the generics. - The status type defines that optionally a data of the type provided by the consumer, a loading flag or an error is returned if something goes wrong.

Let's check the usage on the consumer side:

// src/pages/AnimeDetail.tsx

const { data, loading, error } = useFetch<JikanAPIResponse<RawAnimeData>>(

getAnimeFullById(Number(id))

)

getAnimeFullByIdreturns the url of that endpoint.useFetchin this case will return adataof typeJikanAPIResponsewhich also has different possibilities, in this caseRawAnimeData.

Conclusion

Throughout this article you've seen the most common pain points when it comes to TypeScript in a React project that will pay for the effort, especially when working with others to fully understand the ins and outs of every component, hook and context you need to use. Using TypeScript is investing in code that is more reliable, better documented and readable, less error-prone and more maintainable.

I hope this article helps you avoid pitfalls with this combination of technologies and if you'd like more explanations of other parts of React with TypeScript or perhaps other frameworks like Next, let me know so I can consider including them in part three of this series.

Thanks for reading!